Date/Time

Date(s) - 20/02/2016

7:00 pm

Location

Light House Theatre,

Categories No Categories

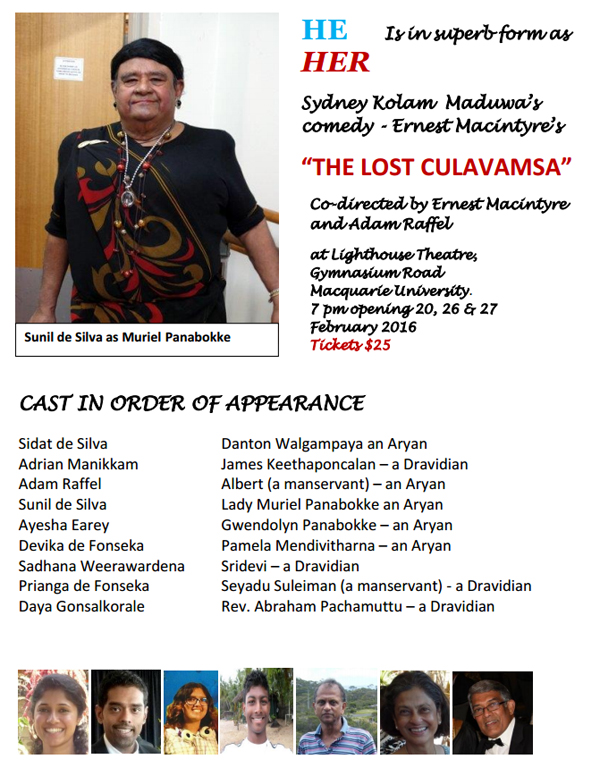

The Lost Culavamsa on 20th February

This play, “The Lost Culavamsa” is derived from Oscar Wilde’s “The Importance of Being Earnest”. Lady Muriel Panabokke who supervises” this whole improbable comedy is based on the most identifiable of Oscar Wilde’s characters; the formidable Lady Bracknell. The whole plot, except for the meaning of ethnicity in Lanka, is transplanted from Wilde’s famous and popular play, with the colours, hues and textures of British Ceylon.

A baby is found inside a mulla1, apparently abandoned, at the seaside railway station of Wellawatte, a suburb of Colombo, in British Ceylon in about 1905. Inside this mulla with the baby is also found a copy of the Culavamsa, chronologically the third in a set of three chronicles of the “history” of Ceylon. The baby, not known to what “race” he belongs, is adopted by a childless wealthy Jaffna Tamil couple, Sir Kandiah and Lady Keethaponcalan, and so grows up and “becomes a Tamil” or for that matter, could have “become a Sinhalese” in other circumstances. He is named James Keethaponcalan by the adopting couple. When this Tamil child, James, grows to be a young man he cannot resist going to the exciting city of Colombo where he is in love with a Sinhalese girl, Gwendolyn, the daughter of the socially and personally formidable Lady Muriel Panabokke.

And in the meantime the grown up adopted James became the legal guardian of a Tamil girl, Sridevi, when his adopting parents passed away. James’s adopting mother had taken charge of Sridevi, her sister’s daughter, when her sister and husband died in a motor accident. The guardianship of Sridevi passed on to James. He takes his guardianship seriously in the way he intends bringing up Sridevi, so James covers up his frequent trips to Colombo for pleasure and for meeting Gwendolyn by inventing a fictitious Colombo brother, named Ernest, who is always up to mischief and in trouble. James goes to the big city regularly to get his “brother” Ernest out of trouble. Sridevi believes this story, and the fictional Ernest becomes excitingly real for her, in her youthful circumstance of confinement to a boring Jaffna life. To enrich the improbability, this characterization of the fictitious brother as an exciting adventurer leads Sridevi to fall madly in love with the fiction. To allow a story that would otherwise come to an impasse with a fictional Ernest, an actual person steps into the fiction of Ernest. James’s best friend in Colombo, Danton Walgampaya, becomes attracted to the adopted Jaffna girl, Sridevi, whom he has never seen but for whom he has had his passions roused by his friend James’s descriptions of her. On hearing of Sridevi’s passion for the fictitious Ernest, Danton decides to present himself to Sridevi, as Ernest.

Danton too is watched over closely by his aunt, Lady Muriel Panabokke who took him as an infant and brought him up when Danton’s mother, Lady Panabokke’s sister, and her husband died. So, whenever Danton wants to go out of Colombo, for his private pursuits, he uses a fictional situation he has created. He has a close Burgher friend, Lembruggen, an actual person, but who is supposedly always ill, to help him sneak out of Colombo, for” Lembaying”, as he calls it.

Pamela Mendivitharna, the lady who was responsible for losing the baby in her paid care, together with her Culavamsa, was a scholar who lived with Mrs Adeline Walgampaya the mother of the lost baby in Horton Place Colombo and in fact looked after this baby while pursuing her research. She was the daughter of a famous Ceylonese archaeologist and epigraphist scholar, Professor Codrington Mendivitharna, and had inherited her father’s passion for the ancient history of the Aryans (Sinhalese) and the Dravidians (Tamils). She soon discovered that the baby she lost was being adopted in Jaffna. She immediately secured a position as governess to look after the baby in this far away Jaffna household. No one, including her employers, the Jaffna couple adopting the little boy, knew she came to Jaffna, as a young governess, not only to escape from Colombo high society, but also, in an act of atonement, to bring up the little James she lost in the mulla all those years ago. As her scholarship evolved assisted by empirical knowledge, Pamela began to doubt the well-held belief of the time that the ethnicities of Ceylon resulted from North Indian Aryans and South Indian Dravidians settling the island as different “races”. James grows up and Mendivitharna later brings up James’s legal charge, the adopted girl Sridevi. As Mendivitharna grows old in the society of Jaffna of which she becomes part, she responds to the attentions of an old Tamil Christian priest, Reverend Abraham Pachamuttu, who, like her, seeks affectionate companionship. It is Rev Pachamuttu, who at the end, concludes that what matters is the meanings behind all the improbabilities in “The Lost Culavamsa” not its improbable stories. He also says that the same applies to some of the improbable stories in our great religions. The play ends as in Wilde’s play, with the two friends Danton Walgampaya and James Keethaponcalan being shown to be blood brothers, but with the crucial variation of how one

brother became an “Aryan” and the other a “Dravidian”.

Why, in this story, is there a copy of the Culavamsa, the third of the great ancient chronicles (the others being the Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa) of the “history” of Lanka, also inside the mulla with the baby? The Culavamsa’s part in the play is a symbol running through the transplanted Wilde story. There is another story, just underneath the Wilde derived plot, a story about the social and cultural constitution of people in Lanka. This is a very Lankan complication that has yet to see its resolution. Such an idea or any parallel to it is not found in Wilde’s original. Mendivitharna’s complex personal history runs alongside and in affinity with a taste of the twisted ethnic history of Lanka, which in structural integration into the play and in performance would be so mixed in to have its flavour blend in without interfering with the delights of the improbable comedy inherited from Oscar Wilde.