ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY YEARS AFTER ROGERS: 1845 – 1995 – By Ranil Bibile

The villagers cower in fear in the darkness of their mud and wattle huts. The slightest sound outside their walls makes them quake. They have seen too many people killed by the towering terror that smashes through the flimsy walls of their huts, to trample men, women and children into pulp.

The flickering light of the chulu* and the bottle-lamp are useless. The electric torch only further enrages and provokes the monstrous creatures. Firecrackers no longer frighten them. Eking out an existence is almost impossible. The crops are devastated by the marauders. Whether one survives the night or not depends on one’s karma*. It is akin to a game of Russian Roulette.

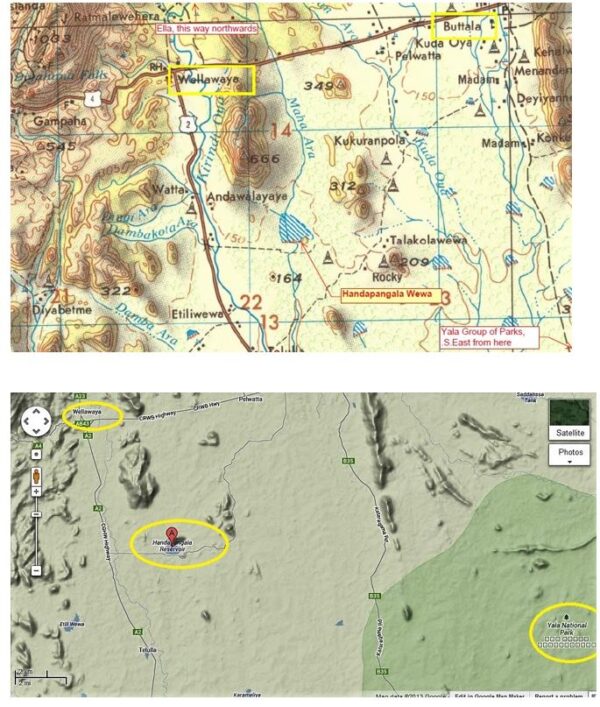

We are just a few hundred metres from the village, lost and apprehensive in the midst of all this terror. Locked inside our vehicle and armed with thunderflashes we are hopefully better off than the villagers. If and when we get out of this place we have something to look forward to; a pleasant drive to Ella Resthouse, a warm bath, a whiskey-on-ice, a hot meal, and a comfortable bed for the night. Our only worries then would be a mosquito or two. For the moment though we are still here, wandering around in the middle of the wew pittaniya*, our spotlight sweeping the distant perimeter of forest and scrub jungle, our eyes searching desperately for a possible exit.

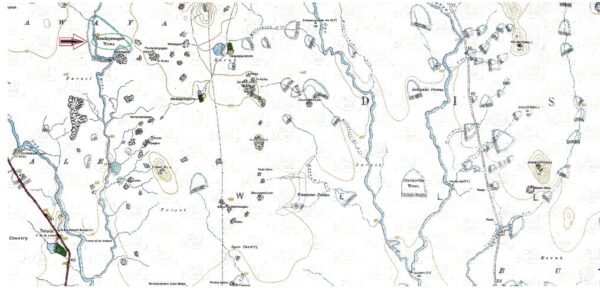

Three hours ago it had seemed such a pleasant place; a grassy parkland lit by the golden light of a late afternoon sun. We had engaged four-wheel drive and low-range gears and wended our way through the billowing grasslands, whipped by the wind coming off the surface of the wewa* – the local lake. The only obstacle had been the dry ara*, a seasonal stream, whose soft sandy bed had immobilized us for a short while until the use of honeycomb matting had given us traction. Having traversed the sandy ara and climbed the steep monsoon eroded embankment on the opposite side, we had parked our vehicle under a tree not far from the water, and waited for the spectacle to begin.

An hour passed in whispers and windsong.

Far across the lake, framed by the blue mountains of Lower Uva, villagers in a catamaran laid a net and thrashed the surface of the ruffled water with their oars to drive fish into the net.

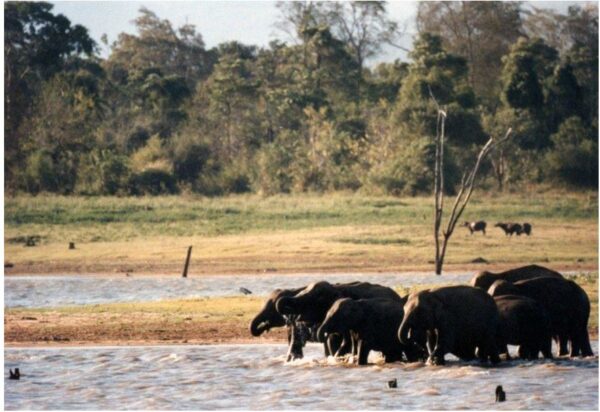

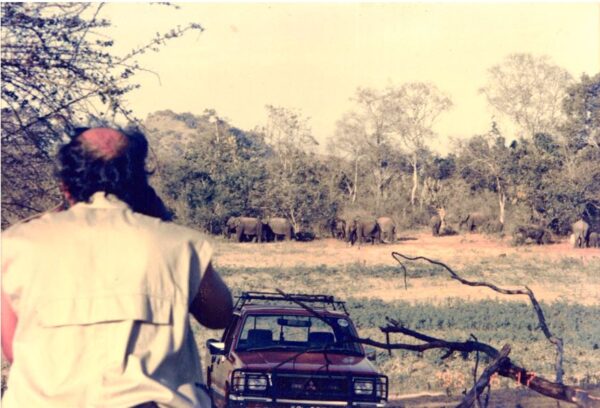

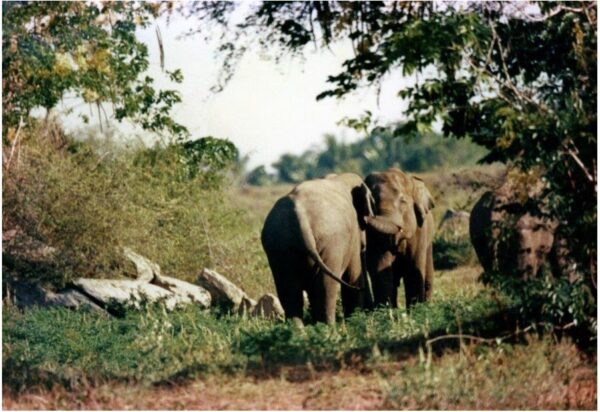

It was not long before the hulking grey forms emerged from the fringing forest to our left with a silence that belied their size, and marched straight into the lake where they began to cavort like playful puppy dogs. They lay down in the water; the little ones climbing on the bodies of the prone adults to roll down with mighty splashes. They sprayed water at each other like little children; they thrashed the surface of the water with their trunks as if mimicking the fishermen. We almost felt like joining them in their playful frolic. Such delightful creatures. So cuddly. Only the villagers, terrorized and cowering in their huts every night, did not think so. But then, they are such ‘illiterate peasants’, really! What do they know about the joys of watching wild animals at play – joys that we city folks travel far to savour?

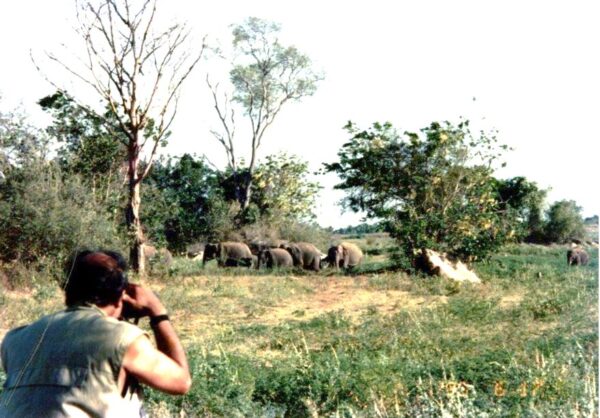

We crept through the swaying grass towards the water’s edge to photograph and film the playful creatures. We had thunderflashes of course, and somebody kept an eye on the forest to our rear, ‘just in case’. Luckily nothing frightful came that way. The afternoon waned. In a while the creatures began to emerge from the water, totally unaware of our presence as the wind was in our favour. As they ambled towards us, we decided that ‘discretion is the better part of valour’ and crept back to the vehicle, concealing ourselves in the long grass as we did so. Since the doors had been kept deliberately ajar we were able to enter the vehicle silently. We pulled the doors to the closed position, and with the latches raised, succeeded in shutting the doors without even the slightest sound. The creatures were getting closer now, moving silently and sedately towards us. We raised the vehicle’s shutters to prevent our smell from reaching them. The thunderflashes were placed on the dashboard with the lighter clasped firmly in the hand. Our deterrent was ready, and we were prepared for an emergency getaway.

Soon we were surrounded by the animals, and had to sit absolutely still lest any movement caught their eyes. They were that close. Around us they stopped to feed for some time. As far as they knew there were no humans nearby to attack or be attacked by. For the moment we had outsmarted them by using the vehicle as a hide. But we knew that with darkness they would gain the upper hand, for we would then lose our main advantage; better eyesight in daylight. To move in the darkness we would need lights, which they could see and attack. Nor could we risk it on foot as they would smell us unerringly, and their great grey forms would be all but invisible to us until we faced a short sharp and fatal encounter. But thankfully, before it got completely dark they drifted off into the fringing forest, seemingly ever so peaceful, as they must have been aeons ago before the ever exploding human population barged into their domain and started a war.

We engaged the motor and slowly headed back to the dry ara. In the last light of dusk, with a fretful eye on the forest fringe and thunderflashes at the ready, we laid out the honeycomb mats on the sandy bed of the ara. By the time we climbed the further embankment it was totally dark, and the stars were out in Lower Uva.

And so here we are, a few hundred metres from the village, trying to find a way out of the wew pittaniya. We have to be careful not to put the vehicle into any of the big holes concealed in the tall grass. Normally, in this kind of terrain, someone would scout the ground ahead on foot. But not here and not tonight. Thus it is slow going, inch by inch, foot by foot. Finally, we reach the perimeter scrub, and after skirting along it for a while, come to a gap. We inch through it and find ourselves in some kind of a narrow village lane, a rutted bullock cart track. For some time since sunset the villagers have been hearing our motor and seeing our powerful searchlight flashing on the trees. As we approach the first hut, six bedraggled people including women and children come streaming out, frantically waving at us to stop. We do so reluctantly, and other villagers from nearby huts come running out too. Questions are thrown at us in rapid fire. Are we military? Are we Wild Life Department officials? Have we got guns? No? Only thunderflashes? But can we stay the night with our powerful looking vehicle with its impressive armament of spotlights and, with our thunderflashes at hand, give them a single night’s respite? Nobody in their right senses comes this way at night so we must have come well equipped to fight off the creatures. Or so they believe.

Little do they know that, having safely enjoyed the spectacle in daylight, we want to now leave this area as soon as possible. But for these are people, every night is a long night; a fearsome vigil as the hours drag on to the whine of mosquitoes and the threat of sudden death from creatures that regularly crash through the flimsy walls of their village huts. Yesterday, one creature did crash through the walls of Jayasekera’s home, demolishing it late at night, hours after sunset. They have no clocks so they cannot say what time the disaster struck. His wife and the two youngest children are still in shock and have been sent to a relative’s hut some distance away. She is refusing to come back and wants to pack up and move to a town somewhere, even to a city slum. This is no life. The fear is palpable. Jayasekera is at his wits end. He has stayed with the two older boys to guard what little is left of their chena*, his only escape from penury now that his hut has been demolished and his jak saplings and banana trees destroyed. Can we please do something for them? If they fight back and the beasts are hurt or killed they will be hauled off to some distant courthouse and fined, and as they have no money to pay the fines, they will go to jail. But no one comes to see what they suffer. No one offers them any compensation for the physical damage to their homes and for the loss of their crops, not to even mention the loss of kith and kin. They plead with us again to stay the night. But of course we are not staying. We are not equipped with guns to deal with these monsters. We only came for the fun of it, and it is time to get out while the going is good. Anyway, we love these animals. They are such adorable creatures. As long as they do not come crashing through our bedroom walls at night.

After dark this dangerous place and these wretched lives seem to be on another planet. The creatures that terrorise this terrain are not the half-tame animals of Yala National Park; these are animals accustomed to kill. For a variety of complex reasons including festering gunshot wounds and constant conflict, they hate humans and are bent on revenge. Just standing outside the vehicle in this place, surrounded by pitch darkness and terrified people, the air thick with omnipresent danger, makes me nervous too. I could do with a double whiskey-on-ice. We give Jayasekera a hundred and fifty rupees to assuage our guilty conscience, pile into the vehicle and head off for Ella Resthouse and its creature comforts. Our ninety minutes of fear are over. For the villagers it is only just beginning. It is yet another long night of terror in their unenviable lives.

It is 1834 in another part of the Province of Uva.

Nineteen years have passed since the fall of the Kandyan Kingdom.

The villagers cower in fear in the darkness of their mud and wattle huts. The slightest sound outside their walls makes them quake. They have seen too many people killed by the towering terror that smashes through the flimsy walls of their huts, to trample men, women and children into pulp.

The flickering light of the chulu is useless. Eking out an existence is almost impossible. The crops are devastated by the marauders. Whether one survives the night or not depends on one’s karma. Even travellers walking on the roads in broad daylight are being attacked. The people complain to the colonial administrator in the person of the Assistant Government Agent cum District Judge cum Commandant of the Military Forces. This person has a gun; in fact he has several of them although he is an indifferent shot. Shooting these monsters is a hazardous business, especially on foot in close foliage on mountain slopes. But the villagers’ complaints are ringing in his ears and he takes his job seriously. With typical British colonial zeal he decides he will take on the challenge and defeat the scourge. He will rid the villages of this menace so that the crops can stand and travellers are safe on the roads. He will remove this obstacle to progress.

His name is Thomas William Rogers, then a Major in the Ceylon Rifle Regiment. The obstacle to progress is the Ceylon elephant. An epic battle is about to begin, which will be wrapped in myth and mystery, and legend and lore, for at least a century and a half to come.

It is 1995 in Colombo. In a leading Sunday newspaper published in the city on 10th September there is an article titled “A Grave Struck by Lightening” in which is asked the rhetorical question, “In today’s context what would have been the punishment for someone like Major Rogers who had killed 1400 elephants?”. And it goes on to state that, “it seems Mother Nature punished him and he was killed by lightening in 1845.”

It is strangely ironic that this article denigrating Major Rogers in the year of his 150th death anniversary sits right next to another article on the same page about a forty-two year old mother of four called V.G. Tikirihamy who had been killed recently by an elephant on her own doorstep in Dambulla, right in front of the terrified eyes of her small children who, cowering in their mud hut, were forced to watch their mother being smashed into pulp.

One is left wondering whether poor Tikirihamy’s surviving husband and children would agree with the Colombo based writer who denigrates Major Rogers as is the fashion today, or would they have given anything to have had Major Rogers standing by their side on that doorstep in Dambulla that fateful day, armed with his elephant gun?

To know the real Major Rogers and the facts about his elephant killing activities let us go back to that period between 1834 when he took up arms against the elephant, and 1845, when he died at the relatively young age of forty-one.

One could be forgiven for thinking that killing an alleged 1400 elephants would have been full time work for one man; but killing elephants was not Major Rogers’ main job. He was in fact primarily a road builder, and a great road builder at that. Additionally, he was an administrator for the British Colonial Government, working as the Assistant Government Agent, the District Judge, and the Commandant of the Military Forces, all at the same time. He was a busy man indeed.

Being an engineer by profession and having known Major Skinner – the greatest road builder that Ceylon had ever seen, it was inevitable that Major Rogers too would be obsessed with road building in an era that saw the country being opened up, not only for the prospects of plantations (those were early days yet) but also for communications and administration and control. He connected Nuwara Eliya with Badulla and then continued this road on to Bibile and through Bibile to Batticaloa on the east coast, a distance of over 200 miles through difficult terrain. He connected Badulla to Ratnapura, all the way through the hills. And he built another road from Badulla to Wellawaya and then continued this road to the south coast at Hambantota. He traced the Lower Badulla Road to connect Kandy with Badulla, avoiding the then arduous climb via Ramboda to Nuwara Eliya and beyond. As he himself used to traverse this track on horseback from Badulla to Kandy, he found it perfectly feasible. This trace however remained only a bridle path as plantations never penetrated the wilds of lower Hewaheta and Walapone during the colonial era, and it later fell into total disuse with the advent of the motor car. It took another 140 years for it to be resurrected as a broad highway, and this was done by the late Gamini Dissanayaka during the construction of the giant Mahaweli Project in the 1980s. Today it is one of the most picturesque roads in the country.

Major Rogers also put up bridges, and government buildings of various sorts, both military and civil. He built resthouses, selecting some marvellous spots which are unique even to this day. As if all this was not enough, he pioneered coffee plantations in Uva. The energy and the drive of the man was legendary.

To appreciate these achievements one has to picture the conditions of the day. Everything had to be done with manual labour. There was no machinery whatsoever. The fastest means of transport was on horseback. There was no electricity and no telephones, and the fastest means of communication was by human runner. The country was unmapped and survey data unavailable. Torrential monsoon rains made rivers impassable, and tracks were blocked by landslides. Added to that were the dangers from malaria and cholera and typhoid and hepatitis; and last but not least, the dangers from wild animals on the roads, particularly the elephants. One can then perhaps begin to grasp the difficulties of getting anything done in those days.

How Major Rogers managed to accomplish all his building activities and complete all his administrative tasks whilst at the same time hunting down 1400 elephants on foot in such a relatively short span of time, is almost beyond understanding. Today’s administrators and politicians, whizzing about in their air-conditioned cars, communicating with mobile phones and faxes and e-mails and working with computers do not manage to get half as much done during a whole lifetime.

Major Rogers’ elephant shooting was a task pressed on him by the pleadings of the villagers in his areas of administration. As he was a bad shot to begin with and failed to hit his first five elephants altogether, it is a wonder he did not get himself killed even before he had started. But, like he did in so many of his other pursuits, he persevered doggedly, somehow finding the time to sharpen his shooting skills, until he could bring down a charging bull elephant with one shot.

When the Prussian Prince Waldemar came to Ceylon in 1844 to shoot elephants for fun, his life, in the face of charging wild elephants, was entrusted to Major Rogers who did the needful, shooting two elephants one after the other, when they came to get His Royal Highness. On another occasion at Nilgala near Bibile when he had been entrusted with the safety of the British Governor of Ceylon, Stewart Mackenzie, he again did the needful, shooting an elephant from which the Governor was trying to hide.

After his initial bad aim had been overcome he mostly felled each elephant with one shot. The one time he failed to do that he nearly paid with his life. This was during the trace of the Hambantota Road, on a day when he had already shot several elephants from a herd which had been hampering the road party. The elephant actually seized him with its trunk, but instead of dashing him to the ground, tried to crush him with its feet. With an amazing presence of mind Rogers feigned death, and the elephant left the “corpse” and moved away, only to be shot by a villager who had been accompanying Rogers. This villager and the others of the road gang then carried Rogers all the way on foot to the Badulla hospital, getting there the following day. With a dislocated shoulder and an arm broken in two places, and with no modern pain-killers to alleviate the agony, such a journey must have been excruciatingly painful. Most people would have given up after such a terrifying ordeal, but within three months Major Rogers was back at work, and once more fearlessly carrying out his campaign against the elephant.

In fact many of his superiors tried to dissuade him from this dangerous work since his skills as an engineer and a builder were far more important to the civil and military administrations of the time. But Rogers simply carried on as if getting rid of the ‘pesky elephants’ from his villages was a duty he was obliged to do. The men, who witnessed Rogers surviving what should have been a fatal encounter with an enraged elephant, began to believe that he possessed a great magic charm, and that no earthly power could kill him.

On the 7th of June in the year 1845 he was on circuit in Haputale with Mr. Buller, the Government Agent of Kandy. There was a short but violent thunderstorm during which the party took refuge in the Haputale Resthouse. When the storm seemed to have passed, Rogers came out to the verandah to give the all clear. In that instant there was a blinding flash of light and Rogers fell dead, struck by lightening.

And thus in a strange kind of way the villagers’ belief that no earthly power could kill him came true; for it was literally a ‘bolt from the blue’ that got him.

It later transpired that the lightening had struck the main mast of the pandal which had been erected for the Government Agent’s visit, and somehow it had struck Rogers too, with the metal riding spurs on his boots acting as conductors to the ground.

He was buried in the old cemetery at Nuwara Eliya, which is now in the Golf Club premises. After his death his loss was felt by all. Talking of Rogers’ responsibility vis-à-vis the roads of the province, Major Skinner lamented that, “after his death it required four men to perform with far less efficiency, promptitude and punctuality than when they were administered by him alone.”

The nature of his going, in keeping with the villagers’ prophecy, gave rise to many legends as the years rolled by. Inevitably the manner of his death got connected with his battle against elephants. One legend had it that he had killed an elephant sacred to a kovil in Haputale dedicated to God Kataragama. Another legend had it that a Buddhist priest he had met whilst out shooting elephants had warned him that he would be struck dead by lightening for killing these sacred animals. To die by lightening, known by the Sinhala phrase “Hena gahala marenawa”* is used as a curse even today. Another legend had it that he had cut down a Bo Tree – a tree sacred to Buddhists – that had stood in the path of a road trace and so had committed a dreadful sin.

Because he was renowned for his excellent administrative abilities as well as for his brilliant road building ventures, a memorial tablet in his name was placed at St. Paul’s Church in Kandy. It says, “In testimony of their respect and regard for his integrity as a man, his ability as a public servant, his gallantry as a soldier, and his amiable, social qualities as a friend.”

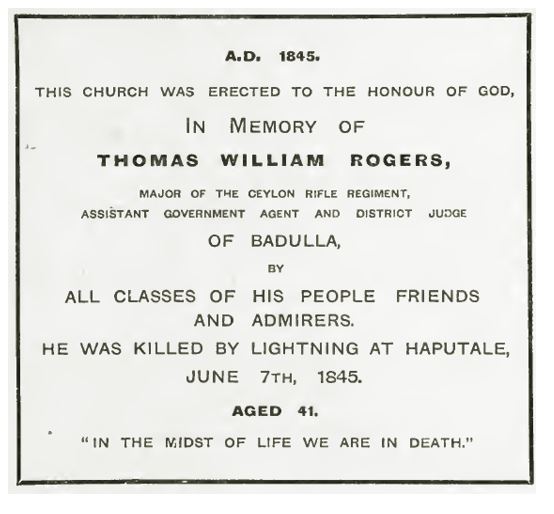

In Badulla there is a church – St. Marks – which was built in his memory and consecrated in 1857. The plate there states, “A.D. 1845. This Church was erected in the honour of God, in memory of Thomas William Rogers, Major, of the Ceylon Rifle Regiment, Assistant Government Agent and District Judge of Badulla, by all classes of his friends and admirers. He was killed by lightening at Haputale- June 7th, 1845, aged 41. In the midst of life we are in death”

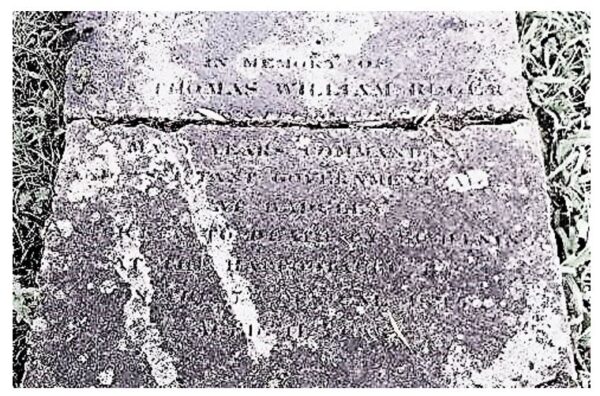

The crack in his tombstone has been attributed to another lightening strike said to have taken place after his burial, though no one witnessed that strike. A conflicting report stated that the tombstone had been damaged at the Colombo harbour whilst being unloaded from a ship. That mystery will never be solved.

As a footnote it is interesting to recall that whilst Major Rogers killed an alleged 1400 elephants in an eleven-year period, in just the two years following his death, from 1846 to 1848, 3500 elephants were killed in the north of the island, and another 2000 were killed in the five years from 1851 to 1856. So Rogers or no Rogers, the elephant was a marked animal. The fact is that they were considered to be pests at that time and the government even paid a bounty for every elephant killed. Times change mores, and yesterday’s ‘pest’ can become today’s ‘endangered darling’. In this context it is interesting to note that the Leopard, which is a highly protected animal today, was considered as ‘vermin’ and legally killed in Ceylon until the late 1950s or early 1960s.

Meanwhile the battle between man and elephant goes on unabated in Sri Lanka’s rural heartland. The elephant of course loses out with each passing year. The human population of the island now stands at 19 million and is growing by over 650 persons per day. Elephants will no doubt fight back here and there and take a few humans with them as they go. This can be attributed to plain bad luck or bad karma for those humans who are in the wrong place at the wrong time. Meanwhile people who are secure in the cities will continue to fight vehemently to prevent the killing of even one elephant, notwithstanding the fact that a particular elephant may be a murderous one, whilst villagers facing ruination and death will continue to consider the animal as a pest and try to kill them even surreptitiously with poisoned bait, when they have no recourse to guns.

When Sri Lanka’s human population has doubled to 38 million within the next fifty years, it is unlikely that even the existing National Parks will be able to survive the onslaught of a land hungry people, and the elephant will be left with nowhere to go.

In Major Rogers’ time the ratio of humans to elephants was very different. But even then the conflict was severe, though very much restricted to the hilly areas as the dry zone plains had been more or less abandoned by the people for many centuries. Today the frontline of the battle has been pushed back to the dry zone plains, a long way from Rogers’ Badulla town.

Major Rogers’ great roads radiating from Badulla to Batticaloa, to Hambantota, to Nuwara Eliya and to Ratnapura are still in use today. His Lower Badulla Road has finally been built. He has a church and several plaques in his memory. And before the 200th anniversary of his death, his task of eliminating the elephant will no doubt have been achieved by the independent nation of Sri Lanka and its burgeoning population.

Of all the wild mega-herbivores that once roamed the earth, only a handful survive in today’s world; the bison, the rhinoceros, the giraffe, the hippopotamus, and the elephant; and Sri Lanka has only the elephant. Hence it will be sad to see it disappear from this small island. But try telling that to the Jayasekeras and Tikirihamys trapped in the front lines of the conflict. They would like to see Major Rogers reincarnated and standing besides them with his trusty elephant gun, any day.

*Glossary:

Ara..…………….Small seasonal stream

Bo Tree……….Ficus religiosa; The species of tree under which The Buddha attained enlightenment, and hence of great religious importance to Buddhists.

Chena…………Usually a field extracted from the jungle by the practice known as ‘slash and burn’ agriculture and carrying subsistence crops.

Chulu …………..A flame-torch made up of dry leaves or chord

Hena gahala marenawa: hena – lightening, gahala – hit or, be hit, marenawa – dying or, to die

Karma…………..Pre-ordained event; ‘fate’

Kovil.……………Hindu temple

Pandal…………..A decorative arch-like structure put up temporarily for special occasions

Wewa……………A lake, in Sri Lanka usually man-made

Wew pittaniya ….The grasslands that thrive on the borders of lakes and lake beds when

the water recedes in the dry season.

Footnotes and illustrations

The gravestone as seen in the grounds below of the Golf Club Manager’s Bungalow

The gravestone as seen in the grounds below of the Golf Club Manager’s Bungalow

“The crack in his tombstone has been attributed to another lightning strike said to have taken place after his burial, though no one witnessed that strike. A conflicting report stated that the tombstone had been damaged at the Colombo harbour whilst being unloaded from a ship. That mystery will never be solved”.

“It was not long before the hulking grey forms emerged from the fringing forest with a silence that belied their size, and marched straight into the lake where they began to cavort like playful puppy dogs”

“In a while the creatures began to emerge from the water, totally unaware of our presence as the wind was in our favour, and they ambled towards us”.

“Soon we were surrounded by the animals and had to sit absolutely still lest any movement caught their eyes. They were that close.”

“Soon we were surrounded by the animals and had to sit absolutely still lest any movement caught their eyes. They were that close.”

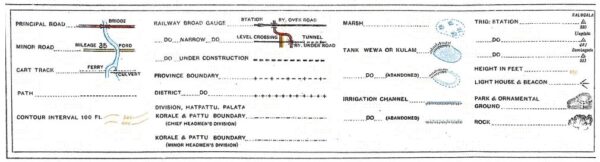

MAPS

Section of the 1947 Survey Department 1Inch:1Mile Buttala Sheet showing Handapangala at top left of map (indicated with an arrow). It shows the surrounding landscape and the ancient long abandoned cascading lakes or ‘wewas’ that were built along the river systems. These were destroyed during the Uva Rebellion which began in 1818. The newer maps do not show this interesting feature anymore.

Map Legend

“They would like to see Major Rogers reincarnated and standing beside them with his trusty elephant gun, any day.”

Further Reading (more current articles)

“The rising death toll over the past four years has made Sri Lanka the worst country for human-elephant conflict in the world”- The Guardian:

“Sri Lanka recorded at least one elephant death a day in the first quarter of 2023, nearly half of them due to human causes, putting the country on track for a record death toll from human-elephant conflict.” – Mongabay

One elephant a day: Sri Lanka wildlife conflict deepens as death toll rises

“Humans and elephants are struggling to coexist. Both are dying at alarming rate” -CNN

https://edition.cnn.com/interactive/2024/04/world/human-elephant-conflict-sri-lanka-cnnphotos/

“People who contend with elephant depredation daily increasingly perceive them as agricultural pests, an unwelcome burden, and a threat to their own survival and well-being” – Springer

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10531-023-02650-7

More current: A Video

From the above article on Rogers written in 1995:

“As we approach the first hut, six bedraggled people including women and children come streaming out, frantically waving at us to stop. We do so reluctantly, and other villagers from nearby huts come running out too…can we stay the night with our thunderflashes at hand, give them a single night’s respite…for whom every night is a long night; a fearsome vigil with the threat of sudden death…after dark this dangerous place and these wretched lives seem to be on another planet”.

Situation on the ground a quarter century later, in 2023: It’s much worse than in 1995: