Minnette de Silva (1918-1998)

Illustration by Suweeja Kumari

Source:Architectural-review

Expressive, unapologetic, and ahead of her time in ecological and participative design, the Sri Lankan architect is considered a pioneer of what she called Modern Regionalism – later to be known as Critical Regionalism

Minnette de Silva had a knack for being at the centre of things. A photograph taken at the 1947 CIAM conference in Bridgwater, Somerset, shows rows of besuited white men and the occasional woman. Among them are Le Corbusier, Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew. In the middle, seated next to Walter Gropius, is de Silva, a diminutive figure swathed in a silk sari and wearing a flower in her hair. She knew the effect she had on people, particularly men, and she used it. Not for her the anonymity of assimilation. Canny, determined and unapologetic, de Silva did more than just exploit her own exoticism. She owned it.

And for a while, it worked. When she came to England to study at London’s Architectural Association (AA), she was an anomaly. Her appearance – always in a sari, hair pinned up – fed into the Raj fantasy of the ‘Indian princess’. The Raj had yet to end in India and Ceylon, (now Sri Lanka) and would have been very much alive in the minds of the young men she studied with, as well as the older men she studied under.

It was in de Silva’s expression of herself that she made the biggest impact. Yet she could not help who she was. She would not apologise for it. Was it her fault that young men fell over themselves, offering to carry her bags and equipment at the AA? Was it her fault that everyone else dressed in drab monotones in those postwar years, making the perfect backdrop for her shimmering presence?

Line up of the 1947 CIAM conference in Bridgwater. Photograph courtesy of RIBA Collections

So this is the paradox: that a woman as infamous as de Silva became in London, as Sri Lanka’s first modern architect and the first Asian woman to be made an Associate of the RIBA, should be so forgotten today. That a woman as unmissable as she once had been should fall unnoticed in the bathroom of her home in her old age, before dying alone in a hospital ward.

By the time de Silva had completed her studies, she had also established links with some of the greatest minds of the 20th century. In her early days studying architecture in Bombay, her professional and social circle included the nuclear physicist Homi Bhabha (father of philosopher Homi K Bhabha) and writer Mulk Raj Anand. In Europe, that circle would expand to include Picasso, Brancusi and many others.

It was in Bombay that de Silva, together with Anand and her sister Anil, founded Marg, the seminal South Asian arts magazine, which is still in existence. Marg provided de Silva with one of her passes to Bridgwater, where she recruited subscribers to the fledgling publication. Marg was also one of the reasons why de Silva struck up conversation again with Le Corbusier in Bridgwater, after having met him the year before at his home in Paris.

First issue of Marg

The Bridgwater encounter sealed their friendship, spurring decades of correspondence between the two architects. Those letters, full of humour, technical banter and yearning are, to some, evidence that they were just friends – and to others, that they were something more. Whether friends or more, they never shied away from expressing their deep affection for one another.

In a letter dated June 1949, some months after she had left London for Kandy in Sri Lanka, de Silva writes: ‘Corbu. So, so long a time without a letter. Have you forgotten altogether the little bird of the Islands … Paris seems so far away and I am very nostalgic for it all’. ‘Oiseau de l’Ile,’ writes Le Corbusier in 1952 from Chandigarh. ‘I am a crow, and crows look at flowers … with passion, but the flowers ignore them … I kiss you, Minnette, to the very tips of your fingers.’

Arts Centre in Kandy, de Silva’s last project, an extension of an existing building

Loggia looking through to the traditional open courtyard, or meda midula, in the Pieris House

It was Le Corbusier’s letters and de Silva’s contacts back in Europe and India (the Gielguds, Oliviers, Henri Cartier-Bresson, David Lean, Mulk Raj Anand, the dancer Mrinalini Sarabhai and many others) that sustained her as she embarked on her architectural career in Sri Lanka. They were her lifeline, and Europe a kind of refuge when things got too much, although she would soon find herself fully occupied by a frenzy of work.

‘For all de Silva’s pioneering thinking and much-vaunted elegance, her reputation for being a “difficult woman” never left her’

The mistake most people make is to fall under the spell of de Silva’s exalted social life and elegant dress sense, and ignore the work she actually did. Her thinking, her ideas about regionalising modern aesthetics, were well ahead of their time. So were her forays into eco-architecture and participatory design, unnamed and unknown concepts back then.

Moving between the capital, Colombo, and her studio in Kandy, de Silva worked on numerous small villas for family friends. Her first project, the Karunaratne House (1947-51), was the earliest manifestation of her building philosophy. She may have felt cowed in the presence of Le Corbusier when she first met him, but when it came to her own designs she was not so retiring.

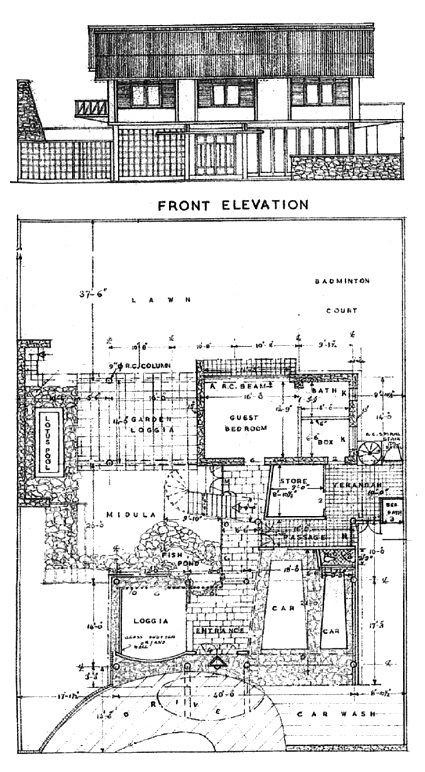

Pieris House drawings

A Modernist at heart, de Silva nevertheless could see its limitations in an Asian context. Rather than break entirely with tradition to import a new language into her building, she saw an opportunity to both revive a waning arts and crafts industry, while modernising traditional aspects of Sri Lankan architecture. Her work was a kind of hybrid, what she called Modern Regionalism, which later came to be known as Critical Regionalism.

‘It is essential for us to absorb what we absolutely need from the modern West’, she wrote in 1950, ‘and to learn to keep the best of our own traditional forms.’ She applied this thinking to the Karunaratne House, hiring artisans to weave Dumbara mats which she used as panelling for internal doors, to fire clay tiles along ancient patterns, and commissioning celebrated local artist George Keyt to paint a mural, which she set into the length of the living-room wall.

Coomaraswamy Twin House in Colombo

De Silva’s first house in Colombo, built for the Pieris family, went further, incorporating the beginnings of an open courtyard into the house’s living space, an import from a previous era in Sri Lankan architecture. This meda midula would become a hallmark of many of her dwellings and would be refined and experimented upon by subsequent architects, most notably Geoffrey Bawa.

Between the late 1940s and early 1960s, de Silva designed and built dozens of homes, including her most Corbusian structure, the Senanayake flats at Gregory’s Road in Colombo. This whitewashed building still stands, its modern exterior softened by the shrubs and trees she had planted in strategic locations, at once cooling the structure while lending it gentle camouflage.

At the other extreme is de Silva’s townhouse for Mrs CF Fernando. A product of her research into low-cost housing and indigenous building methods, it incorporates rammed-earth technology. The house – still owned by Mrs Fernando and located in Colombo’s Wellawatte suburb – is a compact cube whose satinwood staircase and surrounding verandas channel cooling air across its two floors.

Senanayake flats in Colombo show the influence of Corb. Image courtesy of Three Blind Men

Biography

Key works:

Karunaratne House, Kandy, 1951

Fernando House, Colombo, 1954

Pieris House, Colombo, 1956

Senanayake housing, Colombo, 1957

Public housing, Kandy, 1958

Amarasinghe House, Colombo, 1960

Coomaraswamy Twin Houses, Colombo, 1970

Arts Centre, Kandy, 1984

Awards and honours:

Sri Lanka Institute of Architects Gold Medal, 1996

Quote:

‘I was dismissed because I am a woman. I was never taken seriously for my work’

The concise nature of the house and its relatively low cost were reflective of her thinking at the time, as she wrote in a 1955 article: ‘We must re-orientate our ideas for living comfortably in congested towns like Colombo, where we no longer have expansive acres of garden and spacious cool pillared halls.’

Perhaps her most challenging commission was the sprawling and ambitious 1958 public housing scheme in Kandy, the island’s second largest city. It was the chance de Silva had been waiting for and she seized it, consulting extensively with future householders, meeting with them and completing detailed surveys on how they lived. She then used this information to design different housing types, some of which were built by the householders themselves. Today, this kind of participatory and inclusive approach to design and construction is celebrated. De Silva did it without fanfare, always aware that the ultimate success of the scheme would be measured by how useful householders found their new living environment.

The scheme proved a success. It became a model for other housing schemes on the island, although none came close to the original. It also worked on a social level, cementing relations between Buddhists, Hindus and Muslims. As an exercise in building strong, mixed communities, it was exemplary, despite the troubles that would undo the country following independence.

Detail from the Amarasinghe House

Limestone wall from the Pieris House in Colombo

Yet for all de Silva’s pioneering thinking and much-vaunted elegance, her reputation for being a ‘difficult woman’ never left her. Many remember her as inflexible and cantankerous, but at the time, being a woman in a male profession in a developing country was extremely difficult.

Despite de Silva’s achievements, she was never given the recognition she deserved. Instead, those accolades fell to Geoffrey Bawa, known today as Sri Lanka’s foremost modern architect and a master of Modern Regionalism. It is telling that those who remember Bawa, a recluse himself, recount his imperious commands to build a wall here or tear down a wall there with smiling admiration. His demands are seen as the work of a genius and his behaviour simply the product of that genius.

As Bawa came on the scene in the early 1960s, de Silva’s influence declined. She left for Hong Kong and London in the following decade, returning to her Kandy studio in 1979. Her last significant building was the Kandy Arts Centre, constructed in the 1980s. In its original form, it was a true synthesis of her attempts to fuse the modern with the regional. De Silva kept and restored the existing 19th-century building, expanding it in a way that would not disrupt the natural landscape.

de Silva with Picasso, American sculptor Jo Davidson and Mulk Raj Anand at the 1948 World Congress of Intellectuals for Peace

Despite the many changes made to her original vision, one thing remains. The arts centre belongs to the artisans. Their craftsmanship is evident in every corner of the building, from the balusters to the lanterns to the chairs, and the workshops where the artisans themselves can be seen creating their wares. She consistently championed them, integrating them into every project she designed in her 50-year career.

Among de Silva’s last visitors to her Kandy studio was Malkanthi Perera, daughter of Mr and Mrs Pieris, and long-time friend. Perera lives next to the two houses de Silva designed for her family in Colombo. ‘Minnette was always kind and always had time for you’, she says. ‘I shall never forget her last words to me: “I wish more people would make time and come and see me here, rather than come for my funeral.”’

De Silva died in November 1998 aged 80. Just two years earlier, the Sri Lanka Institute of Architects had awarded her its Gold Medal, more than a decade after it had done the same to Bawa. By then de Silva was financially depleted and her Kandy home was decrepit.

Courtesy of RIBA Collections

Today, few of her buildings survive. The Karunaratne House, her first project, is virtually derelict. Her own studio at St George’s in Kandy has long since fallen into ruin. Modest townhouses and villas like de Silva’s have been swept aside in Sri Lanka’s quest for newer, shinier and more vacuous architecture. And so de Silva, this 1940s It-girl, this queen among drab men, this pioneer of tropical Modernism, passed away virtually unremarked, her death as subtle as the buildings she designed.

This piece is featured in the AR July/August issue on AR House + Social housing – click here to purchase your copy today