Towards Jaffna- By Uditha Devapriya

Source:Island

At some point in our childhood, the world beyond Omanthai and Kilinochchi disappeared from view. Our teenage years were filled with memories of maps, flags, terrains, and roads. In the classroom, in the travel books, and across the media, they reinforced the indivisibility of the country. Yet belying that picture of unity was a fragmented polity, one whose contours stretched from the north of the country to the western and southern coasts, skirting Colombo on one side and bordering Hambantota on the other. We never saw this other map until later, but the realities of war forced us to accept its divisions when we did.

My generation came of age when the war had begun to intensity; by its end we were sitting for our O Levels, hardly cognizant of the politics that went into it. Our knowledge, I daresay ignorance, of what lay beyond Omanthai and Kilinochchi was limited to what we saw on TV, when the final stages of the war took correspondents from every station to the frontlines. This was a part of the country we’d barely heard of, let alone gone to. It took the bloodiest conflict in the region, one of the bloodiest in the world, to bring it to our doorstep.

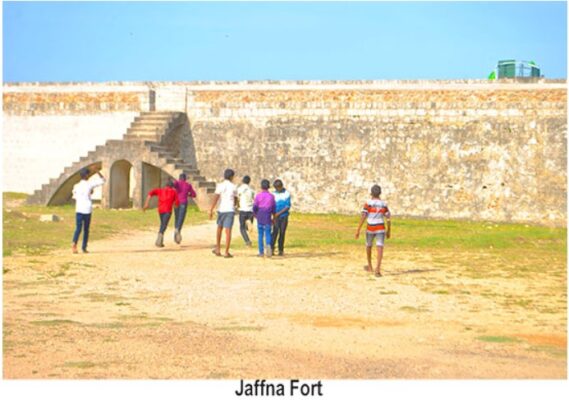

I’ve travelled down south many times, because part of my family lives there, but also because the south opens up to new vistas every time I pay a visit. The Galle Fort never looks, or feels, the same with a second trip: the roads open up to new kiosks, new monuments, new edifices, though they’re no different to what you came across earlier. I’ve also gone up country, partly because of my faith: Kandy never fails to entice, “so airy, fanciful, and obviously suggestive of sweet things”, as Robert Kaplan once put it. Yet if the south’s yellow beaches and Kandy’s hilly redoubts remain etched in the corridors of my memory, if they remain accessible to my mind, and if the memory of travelling there evokes nostalgia even now, no similar sentiment arises when I dwell on Jaffna. I find this troubling, even regrettable, but hardly surprising: the sad truth is that I’ve travelled to the north just twice.

My two journeys unfolded in two different, polarising contexts: the first in the aftermath of post-war reconstruction, the second in the aftermath of the electoral defeat of the party, and person, credited with ending the war. Each transpired against different weather conditions: the northeast monsoon inundating the road in the first, the interregnum between the northeast and southwest monsoon starching our collars with sweat in the second.

It was the weather, not the politics, which transfixed me. Even at its coolest, Jaffna remains warmer than the hottest days in Colombo: it hardens concrete and scorches skin, transforming the region into a sun-baked expanse from which no shelter is possible. The heat cools down the further you go from the city, but even in the palm-thatched paths of Jaffna’s villages, it has a way of discovering you and forcing you into shade. In the former lair of the Sun God – Prabhakaran’s moniker – it remains impossible to hide from the sun.

My friend Fadil Iqbal, who cycled across the country with a couple of friends in 2018, told me that he came across the most beautiful sight from his entire journey here: women in saris, cycling their way to work and shop. But the bicycle is far, far from the only ubiquitous thing in Jaffna: the roadside kiosk, guesthouse, paṉai maram, and Kavadi Aattam occupy special places as well. I couldn’t spot out one Mercedes or Audi, not even a second-hand SUV: most people seem to prefer budget cars and vans to more Veblen varieties.

In fact, despite the intrusion of government aid and private capital, consumerism does not appear to have taken root: people walk, cycle, or take the bus. Probably no other region in the country boasts of university deans biking their way to work. They do so here: a legacy not so much of personal thrift as of the enforced privations of a war.

Whether this will change remains to be seen. To be sure, nothing much had altered between my first and second trips: the same sun-baked people took the same buses and bicycles, no doubt visiting the same places. Public transport is in much better shape here: not in the best of conditions, but an improvement over public buses in Colombo. In its own way, that reflects the consumption patterns of the population: consider that the Northern Province contributes the lowest regional share to the country’s GDP (Rs 586 million in 2018, compared with the Eastern Province’s Rs 813 million and the Western Province’s Rs 5.5 billion). Consider, also, that the region bears the smallest number of vehicles in the country: 272,285 in 2018, fewer than the 374,799 in the more depressed Uva Province. No wonder, then, that three-wheelers are hard to find and harder to hail: that same year, the region boasted a little more than 21,000 of them; Uva, by contrast, had well in excess of 70,000.

If these statistics offer a snapshot of life in Jaffna, they by no means essentialise the people around whom they revolve. It’s difficult to pin them down to a specific conception of them, not so much because they’re unwilling to lend themselves to conceptions as because nowhere can one find a people willing to let others define them.

From political views to perceptions of outsiders, the people of Jaffna view different things in different ways, through different perspectives and prisms. I realise that this in itself is a gross simplification, so I hasten to add that diversity doesn’t necessarily imply disjuncture: there is a certain framework within which, for instance, they see the politics of Colombo, even if they share diverse opinions. Some hardly bother with politics; others bother themselves with little else. Yet debate, no matter how tenuous, always ends up on a definite point: there’s never a sham show at impartiality, the sort we’re used to. “You always feign ignorance or neutrality when talking about politics,” a university lecturer complained to me. “We find that tiresome, so we take sides. How can you remain neutral with these matters?”

All this translates into unpredictable voting patterns. Asoka Bandarage in her seminal study of the war in Sri Lanka rightly warns against seeing the conflict as a tussle between two racial groups: there were, she explains, important cleavages within these groups, based on class as well as caste. Roughly the same can be said of the political views of the people of Jaffna: a microcosm of the complexities of that conflict itself. Jaffna was, after all, the only division J. R. Jayewardene lost in 1982, trailing behind not just the Tamil candidate, the ACTC’s Kumar Ponnambalam, but also, incredibly, the Sinhala candidate, the SLFP’s Hector Kobbekaduwa, and this a year before the horrendous anti-Tamil pogrom.

The reason for that isn’t hard to find: depressed, impoverished, and deprived of a proper mechanism through which prices could be guaranteed for their produce, the Jaffna cultivator voted for the candidate of the party that had put such a mechanism in place while in power. The Jaffna youth, on the other hand, voted for separatism: ironically, in the view of certain historians, a result of the same party’s policies regarding university admissions and district quotas, policies which hit the petty bourgeoisie from which that youth hailed. Historians get it wrong about those quotas, though: they hit some communities more than others, but again, as Bandarage has observed, these disparities were as much rooted in class as they were in race: while admissions from the Northern Province dropped, so did admissions from urban centres elsewhere, while opportunities for the more depressed Eastern and Estate Tamil populations increased. Commentators are divided over to what extent these groups felt these changes, yet that should not belittle the fact that their impact was hardly the same everywhere.

Even now the rift between Sinhala and Tamil communities has failed to eliminate rifts within these populations. In Jaffna, as in other regions caught between rural outposts and urban centres, the peasantry seems to occupy a world different to the world occupied by the petty bourgeoisie, from whom the rhetoric of separatism, not unlike the ultra-nationalism of the Sinhala middle-class, continues to emanate.

The Jaffna cultivators hardly prospered under the LTTE. But the war’s close has not brought them any closer to the prosperity they thought they’d achieve after its end: as a news report from three weeks ago makes it clear, 12 years after May 2009, Jaffna farmers continue to be squeezed of fair incomes and fair prices by an unofficial trader imposed 10 percent levy: one originally imposed in the 1980s, ironically by the LTTE. If this doesn’t quite turn cultivators to voting patterns at odds with those of the Jaffna middle-class, it nevertheless compels them to welcome any resolve on the part of the government, whatever the party, to free them from these shackles, including the onerous import: thus while much of the country complain about the government’s restrictions on imported crops, the Jaffna Potato Growers’ Association has welcomed those restrictions, claiming it would protect the community. One wonders whether mainstream Tamil parties have addressed their concerns: if not, and if barely, it shows how the racial dimensions of a conflict tend to belie its class/caste dimensions. Perhaps we should give pride of place to the people who really matter: the farmer, not just the trader.

In A Passage to India, the two woman protagonists say they want to see the real India. What officials prepare for them is anything but the real India: it’s the India of Orientalists and the British Raj, a country limited to a colonial canvas, an occasional encounter. To get to the real India, the women realise they must first get out of the India they are in. This is true of Jaffna too: to see Jaffna as it is, and not as it is made out to be by travelogues, one should escape the cloistered quarters of hotel rooms, city streets, and roadside kiosks.

Twelve years after the war’s end, I’m not entirely sure whether we’ve come to terms with perhaps the most enigmatic place in Sri Lanka. The people here are hard to square, to rationalise, or to predict. Their view of the world is radically different to ours: a fact that, more than anything, should bring us closer to them, given how much we are in need of a different perspective. In all its complexities, its many dimensions, its many borders – real and imagined – we should thus endeavour to go to Jaffna: in the name of our future, and our national reconciliation: that ever elusive thing we all try to realise, but fail to, after all this time.