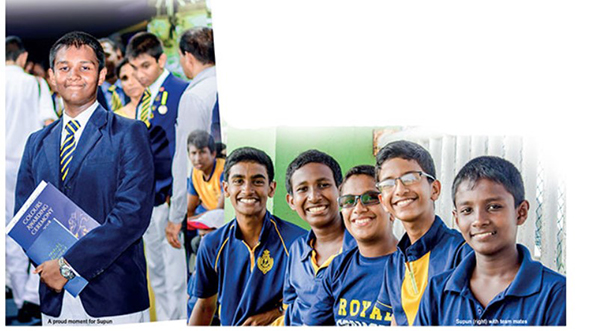

SUPUN JAYASINGHE’S RITES OF PASSAGE-By Uditha Devapriya

Source:Island

Situated at Stanley Wijesundera Mawatha, the Planetarium continues to captivate and fascinate, yet unless you strain your eyes, you can easily miss it. It’s one of those places you go to, through a prior appointment, and emerge from wishing you could go back in again. I must have been in Grade Five when I visited it on a class trip in 2004. Supun Jayasinghe was in Grade Five, too, when he went there with the rest of his class seven years later. The only exception, apart from the year of the visit, was where he came from: a 100 miles away, in Dambulla. It was the first time he had been to the city.

Intriguing and exhilarating as such a trip may have been, he had other things in his head. A few months later, he wouldbe sitting the Grade Five Scholarship Exam. How would he study for it? What marks would he score? Where would he go, if those marks turned out to be high? These questions nagged him, yet for the moment he let them off.

In any case, the ride had been exhausting: having started at four in the morning, it was about nine when the bus entered the city. It made its way to Independence Avenue, and from there towards the University of Colombo.

In any case, the ride had been exhausting: having started at four in the morning, it was about nine when the bus entered the city. It made its way to Independence Avenue, and from there towards the University of Colombo.

Between Independence Avenue and Stanley Wijesundera Mawatha, the Race Course faces Royal College. Intrigued by the Arcade, then the College, Supun and his classmates turned to their teacher. Standing up, he looked at them and described what they were, laying emphasis on the school more than the complex. Having described it in detail – the oldest public school, the most popular such institution, and so on – he brought the discussion back to his audience. “You have your scholarship exams this year,” he reminded them. “Try scoring as high as you can, because if you do, you’ll get a chance to come and study there.”

The memory of those words remained in Supun for a long time. The moment he heard them, he vowed to get as high a mark as he could, to get that chance, to come here.

Whatever the shortcomings of the Scholarship Exam may be, there’s no denying that it has opened up a world of opportunity for an aspiring lower middle-class. Supun’s father, a businessman, and mother, a teacher, hailed from this middle-class. Having attended a local Montessori and a Model School, he spent the whole of 2011 studying for the exam, forfeiting what little free time he had poring over books under a tree in his front yard. Yet, while he hit the books as hard and as much as he could, he did not push himself to compete with his peers. He’d told everyone he would ace the paper, but that owed less to a desire to be the best in the class than to a yearning to enter the best school he thought there was.

In any case, he got what he wanted. The marks came home somewhere in December 2011: having aimed at 180, he had scored 186. An even better piece of news came soon afterwards: the cut-off mark for Royal in 2012 happened to be 182. This meant only one thing: he would be boarded at the College Hostel, the following month, the following year.

The decision to go to Colombo did not come easy. Supun’s mother had opposed it at first, claiming it was too far. The marks were what convinced her. Even so, going to a city he’d only heard about and seen just once, and choosing to stay there for the better part of the next seven or so years, was a challenge. How would he fit in? What would he have to adjust to? Did people act there the way they did here? Did they differ in how they studied, read books, wrote answers? How they ate, drank, walked, and talked? He had much to think about, and as the weeks drew the year to a close, not much time to think them over.

Before everything, of course, there was the question of visiting the Hostel. On January 8 a letter arrived at his home, notifying them that the new term would commence a few weeks later, and that an orientation would be held before it did, on January 20.

Excited as he was, Supun nevertheless felt uneasy. On January 19, he and his father made their way to a rented house at Mount Lavinia, where a not-so distant relative lived. The next day came slowly, excruciatingly slowly. “I couldn’t sleep, I did not want to,” he remembers it today. Somehow, the night passed, and the following morning, having consulted and checked out at an auspicious time, the two of them made their way to Colombo.

Sri Lanka’s public schools, in particular those whose origins go back to the 19th century, are distinctly British in their architecture. The historian K. M. de Silva not unjustifiably calls it bland, unremarkable, and passé, when compared with Portuguese and Dutch architecture. For all their blandness, though, the British invested these buildings with an aura of expansiveness, with corridors giving way to gardens, quadrangles, and still other corridors.

Finding their way through an endless maze of entrances and exits, Supun and his father could not locate the Hostel. When they finally did, they were ushered into an orientation. Supun remembers two things from that day: his new class (6N), and the school song. The latter awed him: he hadn’t listened to many English songs, let alone school anthems, until then.

Having returned home after the orientation, father and son were told that the new term would begin five days later, on January 25. The second time around they came to Colombo in a car. Starting the journey of more than a hundred miles at four in the morning, they arrived at their destination at one or two in the afternoon.

At the Hostel the usual procedure was followed. The seniors directed him to his room. Each room had bunker beds. Not used to sleeping on them, he chose the first compartment, sharing the bunker with three others. When the last of the parents left, he predictably felt his nerves on the edge. The old fears returned: would he be able to fit in?

As with all public schools located in the city, the history of Royal College has woven itself into the history of its surroundings. Confusing at first, its topography extends from one end to another, covering a great many sites. To socialise into and familiarise himself with such an environment physically was not, however, tough for Supun. The real challenge lay elsewhere: the all too ubiquitous presence of English, and the melange of race and religion within the classroom. In other words, language proficiency plus cultural assimilation.

Glancing through his achievements from then, it struck me how his resolve stood out in them all. Back in Dambulla he had neither let the achievements of his peers ruffle him nor allowed himself to be overtaken by a desire to do better than them. He always, for instance, came first at his first school, but not because he wanted to beat everyone else to it; he just wanted to do something, and when he put his mind to it, he tried to do it somehow, on his own.

In Colombo this remained his philosophy. Whether it was winning creative composition and literary criticism prizes, becoming Junior Prefect (2015) and Junior Steward (2018), right before winding up as Steward (2019) and Chairman or Secretary of a great many clubs and societies (to list just some: Philatelic, Science, Library Readers), he let himself into whatever he took a fancy to. He did not, however, abandon his academics; studying for his O Levels, he ended up with nine As. Needless to say, on the field and in the class, at studies and sports, he confronted, and got over, those two challenges of proficiency and assimilation.

Supun’s story, I realise when I read through it, at once reflects and deviates from the norm. Reflects, because it conforms to the general pattern (initial difficulties at getting used to life in the city being followed by assimilation into the cultural and social patterns of that city), and deviates from, because his willpower is hard to find among his peers, or at least most of them. There is a reason for that: born with congenital anomalies on his right hand and leg, he has refused to let them get in his way, having won medals at the Para Games (2018) as well as for volleyball, boxing, table tennis, hockey, baseball, scouting (with a President’s Badge in 2019 to boot). By all accounts, this is to be admired, as it should be even now.

Steven Kemper dedicates the last chapter of his book on advertising in Sri Lanka (Buying and Believing) to a Sinhala lower middle-class family, residing in the outskirts of Colombo, who manage to realise their aspirations through their second son gaining entry to Supun’s school. Kemper, ever sensitive to the vagaries of class, points out how two-pronged entering a better school can be: a “singular opportunity”, yet one that comes with the price of accommodation “in a hostel.” Boarding their son, the family later relocates to Colombo. They make that move because they have to: the son is their link to the city, and to all it represents.

This country is home to a great many families who aspire for a better life, and one way through which they seek that life is education: not merely what you study, but where you study. Supun’s case is therefore illustrative: it’s the story of every other middle-class child. What’s interesting is how their integration to the city has brought about a transformation in the country’s elite schools. In that sense Supun’s story, as with that of the family in Kemper’s book, is not only illustrative, but also instructive. A Senior Prefect today, waiting for his A Level results, he finishes the conversation with a simple personal credo: “I’ve always aimed high and big, and I think I’ve always got there.” I am inclined to agree.