NILGALA FRONTIER – by Ranil Bibile

NILGALA, where Raja Singha, Lord of the Tun Sinhala, vanquished the man-eating crocodile, was a dead end.

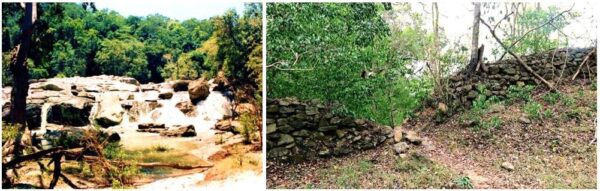

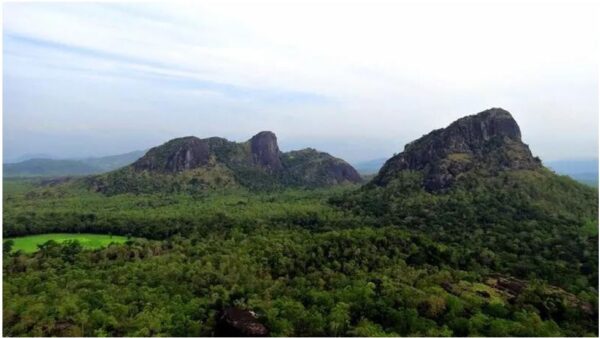

ONCE, many years ago, whilst exploring this roadless terrain on foot, I came across the remnants of an ancient hewn-stone fortress. It was situated on a rocky rising rib of land between the roaring river and the brooding peaks of Ulhela and Berayahela, and half buried amidst the tumbling boulders and man-high mana grass of this place. I had just begun to investigate the crumbling battlements when a herd of elephants approached me, forcing me to retreat towards the waterspread of the Senanayaka Samudra.

Though I longed for years afterwards to return to this remote ruin, to touch the stones once again and feel them come alive with the history they must have known, it was not to be. As the years went by, I passed oft times within a league or two of it on my many restless wanderings the Maha Vedirata. Yet I never set my eyes on it again, and often wondered as to who had built it and for what purpose it had stood there in those deep and forlorn forests, beyond the back of beyond, with nary a village or human settlement for miles around. Had it guarded a city that still lay undiscovered and unrecorded in our chronicles, perhaps lost in the mists of time? If not a city, then perhaps a great highway? But if so, then a highway from whence to whence? For today, only an elephant trail brushes past those ancient stones and vanishes into the tall grass that rustles gently in the winds that blow across the waters of the Samudra and up the canyons of Makaré.

THE year was 1602 A.D. The Portuguese held sway over the maritime provinces of the island, especially in the west. In the rugged mountains, the Kingdom of Kandy held out against the invader and lived its life of independence a hundred years after the first Portuguese men of war had landed. The King of Kandy – Vimala Dharma Suriya – the former Konappu Bandara, wished however for an ally to oust the Portuguese, and in the process struck upon the Dutch. And thus came to the shores of Ceylon the Dutch admiral Joris Van Spilbergen the first ambassador from the Prince of the House of Orange, to the only potentate in the east who claimed to wear a crown. A journal of this embassy kept by an officer of the expedition stated that the journey from the roads of Batticaloa where the Dutch ships dropped anchor, to the kingdom in the hills, was made through Nilgala, Wegama and Alut Nuwara. Reading that account, I felt that it may be a clue as to why there was a fortress in Nilgala. For, if Nilgala had once been an important way station on a route from the east coast to the Kandyan Kingdom, then a fortress may have been essential.

In 1620 A. D. the Danish admiral Ove Giedde too dropped anchor off the east coast of Ceylon and according to his journal he journeyed to Mahiyangana to see the King, passing through Nilgala and Bibile.

A Tálipot Sannas, extant, has it that during the reign of King Rajasingha I, a Veddah chieftain by the name of Maha Kaira Wanniya fought on the King’s side against the Portuguese, and as a reward his sons were granted, on the Sannas, the village of Bibilegama in the Wellassa division in 1611 A D. They settled down at Bibile, four leagues from hoary Nilgala, and for generations thereafter ruled the area. In all that time Nilgala remained an important junction, right up to the Nineteen Hundred and Thirties when the late C. W. Bibile, the last Rate Mahattaya of Bibile-Wellassa – a descendent of Maha Kaira Wanniya – used to bivouac at the old Nilgala and Embilinna Circuit Bungalows with his bullock cart caravan whilst on circuit of the Maha Wedirata.

But the history of Nilgala and The Valley goes back by the millennia.

Dr. R. L. Brohier stated that; “Dim traditions supported by other evidence associate the Gal Oya Valley with man of the Old Stone Age ….this naturally refers to wild untamed Ceylon, long before its history began to be told in lithic record and monument.” Elsewhere he stated; “Apparently in times long past there were along the banks of the Gal Oya several natural hollows or villus..…was consequently of much importance in Pre-Christian times”. Parker talked of “several reservoirs in existence there in the first three centuries Before Christ.”

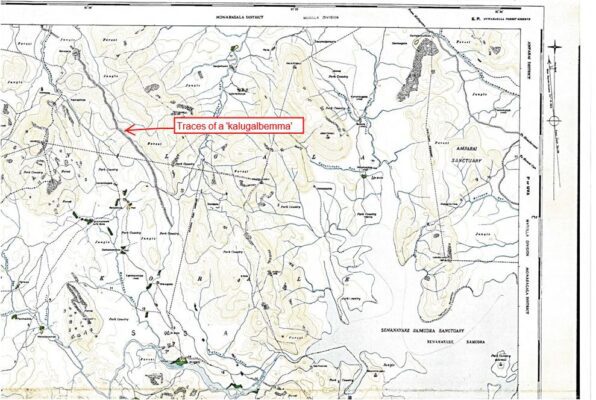

As for myself, I have seen in this region, the traces of a ‘Kalugalbemma’ which the timeless oral traditions of the villagers’ claim is the remnant of a great highway which ran from the Raja Rata in the north to the Kingdom of the Ruhuna in the south during the dim distant past.

North to south and east to west, Nilgala was a crossroads: Once upon a time so long ago.

THE centuries had rolled on.

From the ‘Pre-Christian’ eras, through the times of the Veddah peoples, to the coming of the Sinhala race, and the heyday of the Kandyan Kingdom, and through the invasions and embassies of the Portuguese, the Dutch, and the British, as men and armies had come and gone, Nilgala had been there and seen it all, and remained, as always, a very beautiful spot upon this earth.

It was the British who explored the region most after the fall of the Kandyan Kingdom and left many a written paean to its lure.

Sir Emerson Tennent talked of, “open glades and forest scenery…..park like meadows and surrounding woods… trees of majestic dimension and pastures through which the deer troops in herds. ”

Sir Samuel Baker in 1848 said, “I cannot describe the country better than by comparing it to a rich English park, watered by numerous streams and large rivers, but ornamented by many beautiful rocky mountains, which are seldom to be met with in England. If this part of the country had the advantage of the Newera Eliya climate, it would be a paradise. ”

Governor Sir Henry Ward who travelled down the Gal Oya through Bibile and Nilgala in 1857 had this to say: “All that nature can do to make a country attractive by the most beautiful combination of Mountains, Forests, Rivers, Fertile Valleys and rich grazing grounds upon the Hills is to be found here scattered with a profuse hand”.

Thus did many an explorer write of Nilgala.

BUT everything is impermanent and must change even after millennia. By the Nineteen Hundred and Forties Nilgala was only a small hamlet by the river. In that time disease and dissension wrought havoc upon this place, and its people abandoned it and scattered to other outlying settlements with melodic names; to Hamanawa and Pammedilla, to Maladanambe and Damunuwinna, and further afield. The historic whitewashed mud and wattle circuit bungalow was all that remained, decaying peacefully in the shade of a huge mara tree amidst a grove of jak and plantain trees overlooking green fields of paddy now worked by the goviyas of Bulupitiya. Across the paddy lies a line of stately Kumbuks along the banks of the Gal Oya, from whence emanates the soothing music of waters rushing over the huge granite slabs of the river, for which reason this spot called Lokgal Oya by the locals.

THEN, as the 20th Century reached its midpoint, mechanical monsters the like of which this isle had never seen, descended upon a spot of land below a rock called lnginiyagala to the east of Nilgala.

And they changed the face of the earth.

The dramatic rock of Inginiyagala was married to another hillock a mile away, and thus were the waters of the Gal Oya, which had flowed untrammeled through this valley since the earth was first formed, trapped and hindered on its journey to the sea.

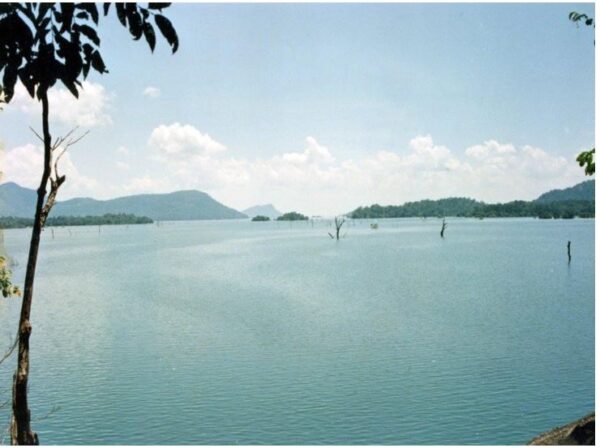

As the pent-up waters rose relentlessly over the monsoon seasons they submerged tens of thousands of acres of beautiful earth; and the historic lands around Nilgala, of Wellassa, and of the Maha Wedirata, drowned.

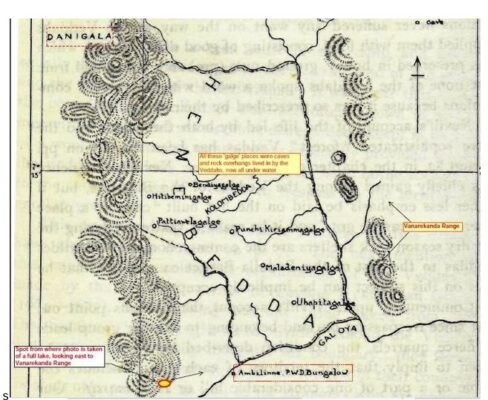

The lands which had been the home of the Veddahs for many millennia, the cave homes to which they had given strange sounding names such as Bendiyagalge and Hitibeminigalge, Uhapitagalge and Punchikiriammagalge, drowned.

The lands over which the great highways had rolled in the kingdom times of the past, drowned. They had been highways from the Country of the Kings – the Rajarata – to the country of the Ruhuna, and highways from the ocean roads of Madakalapuwa to the mountain kingdom of the Kandé Udarata. They drowned.

The glade-like lands of Aralu, Bulu and Nelli, that had been the medicinal gardens of the old peoples, drowned.

The historic circuit bungalow at Ambilinna drowned.

When the new Sea of Senanayaka grew to its full extent, its meandering waterspread covered the the Maha Wedirata to the east, and Nilgala became a cul de sac – a dead end.

The Nilgala circuit bungalow crumbled. It’s water well came to be occupied by dead animals. And Nilgala died.

The fortress had even then been a century and a half entwined in jungle vines

BUT out of this death, a new life arose.

Beyond the canyons of Makaré, and deep in the heart of the Nilgala Frontier, river, lake, and mountain met with great beauty and harmony.

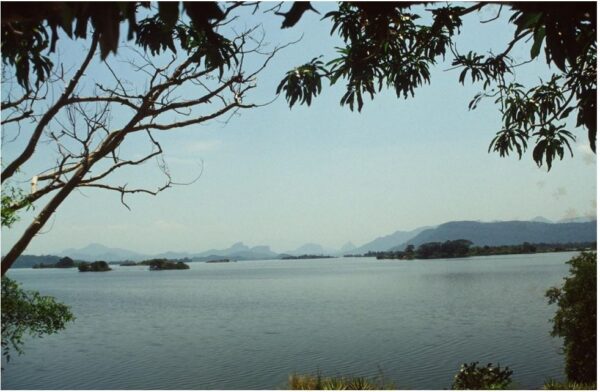

The waters that drowned the great vale became home to teeming aquatic life and were fished by birds that swooped down from the sky and by men who sailed their outrigger canoes through the quiet meandering bays and the windswept open stretches of the biggest lake in Lanka.

The waters that were pent up behind the Inginiyagala Dam were allowed to leave the lake only by generating power for the people. In the lowlands to the east, these self-same waters made thousands upon thousands of paddy acres green, set little subsidiary lakes aglitter with replenished waters, and made old and dying villages resurgent once more.

Even the great groves of trees that drowned and died in the new Sea of Senanayaka, became breeding grounds for countless flights of aquatic birds. The sylvan glades and deep forests of the upper reaches of the lake became havens for elephants, buffalo, deer, sambhur, and all the other creatures which inhabit our forests; blessed at last with a perennial supply of food and water.

But when the rains are late in the season and the lake low in water, there emerges the ghosts of the lakebed – the desolate cave-homes of the Veddahs and their gaunt granite outcrops, the highways of history, and the signs of man from the Old Stone Age. In its upper reaches, the lakebed briefly turns into a brilliant carpet of green grasses and wildflowers, and the grazers and browsers come out to feed in the morning sunlight, walking nonchalantly over ground that man had once ruled with great power and confidence.

ONCE upon a time so long ago, after the fall of night in a fortress far away, the metal of soldiers’ armour clanked and glowed in the flickering torchlight as traders and travellers from the far corners of the isle of Lanka met and ate and drank and gossiped over a chew of betel beside the hewn stone battlements. As the night grew deeper, one by one they fell asleep, lulled by the soothing sounds of the waters of the Gal Oya rushing over smooth boulders. Perhaps they were occasionally disturbed by the tinkling of a pack bull’s bell or the neighing of a soldier’ s horse.

If you spend a moonlit night there today, you will still be lulled to sleep by the soothing sounds of the waters of the Gal Oya rushing over its smooth flat boulders. But if you are disturbed at night today it will be by the trumpeting of elephants or the wild and unforgettable cry of a pack of jackals howling at the moon.

Nilgala lives.

FOOTNOTES, ILLUSTRATIONS, MAPS

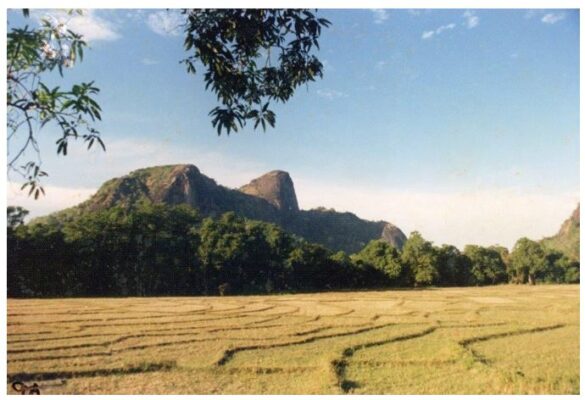

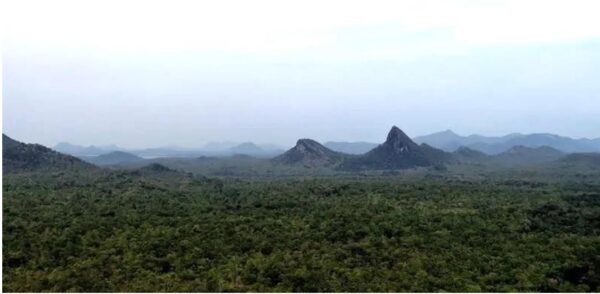

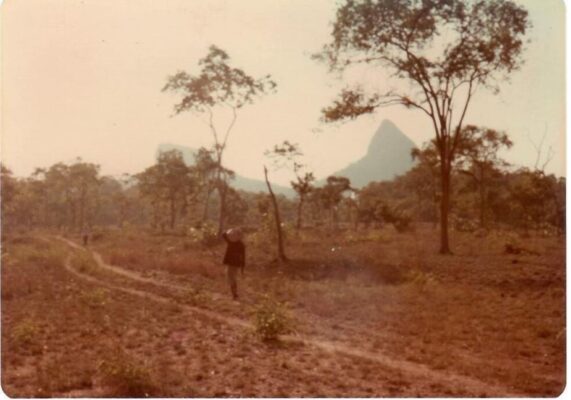

Nilgala talawa – a unique landscape

The medicinal Aralu, Bulu and Nelli trees still flourish in the talawa which is above the waterline.

Sir Emerson Tennent talked of, “open glades and forest scenery….park like meadows and surrounding woods… trees of majestic dimension and pastures through which the deer troops in herds ”

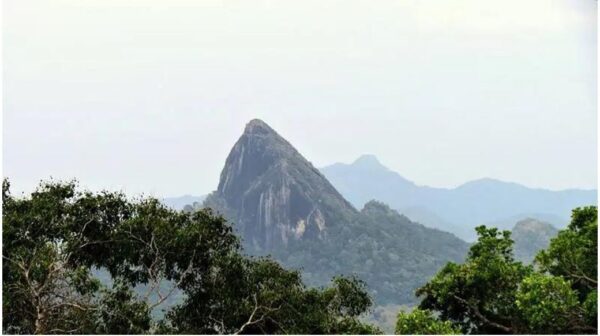

“…overlooking green fields of paddy now worked by the goviyas of Bulupitiya. Across the paddy lies a line of stately Kumbuks along the banks of the Gal Oya and beyond rises the dramatic peak of Nilgalahela (1582 f t – as high as Kandy )

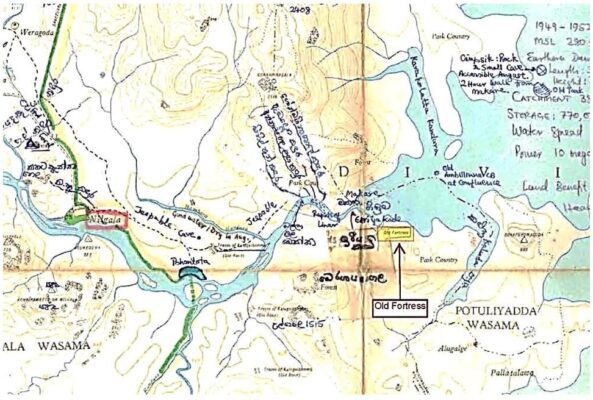

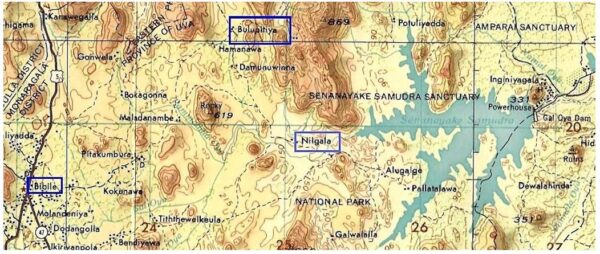

Above: The location of the old fortress, strategically placed at the entrance to the Canyons of Makaré – the ‘Mouth of the Dragon’. The names of the streams not named on the Survey Department’s 1”:1mile map have been entered by hand by the Author, based on his tracker’s local knowledge. The jungle trackers who wander the talawa have names for each and every stream and rock outcrop as they are the navigational waypoints in the trackless talawa.

Below left: Upstream from the Canyons of Makaré there are unnamed rapids, not marked on any map. I gave it a name on my copy of the map for my own reference.

Below right: The remains of the hewn-stone fortress: “It was situated on a rocky rising rib of land between the roaring river and the brooding peaks of Ulhela and Berayahela, and half buried amidst the tumbling boulders and man-high mana grass of this place.”

This Nilgala map sheet shows the traces of the ‘Kalugalbemma’ which the timeless oral traditions of the villagers’ claim to be the remnants of a great highway that ran from the Raja Rata in the north to the Kingdom of the Ruhuna in the south. This feature appears on several of the old 1”:1mile topo sheets of the Survey Department which were compiled in an era when surveyors traversed the country on foot and recorded each geographical feature on the ground. This feature lies under the tall mana grass, and modern aerial and satellite mapping simply does not pick it up or show it.

“Wilhelm Geiger, the brilliant linguist who translated the Mahāvaṃsa from Pali into German, travelled to Sri Lanka three times from 1895 onwards. His interest in the historical background of the Dīpavamsa and Mahāvamsa brought him, on his second trip (1925-1926), to Bibile in search of lost notions about the age-old overland trade routes which started from the north of India and went along the Indian west coast up to the ‘Pearl Island’ Sri Lanka, the important center of overseas trade. Geiger, like von Eickstedt, developed a friendship with Charles William Bibile, Ratemahattaya whose intimate knowledge of forest paths helped him – Geiger – to discover the remnants of an old route leading from Anuradhapura

through the Ruhuna kingdom down to Tissamahārāma on the southern coast”. (Bibile et al Heidelberg “Return of the Ancestors”). It was this Kalugalbemma“ in the Maha Vedirata that the Author’s grandfather, C.W.Bibile, showed Geiger.

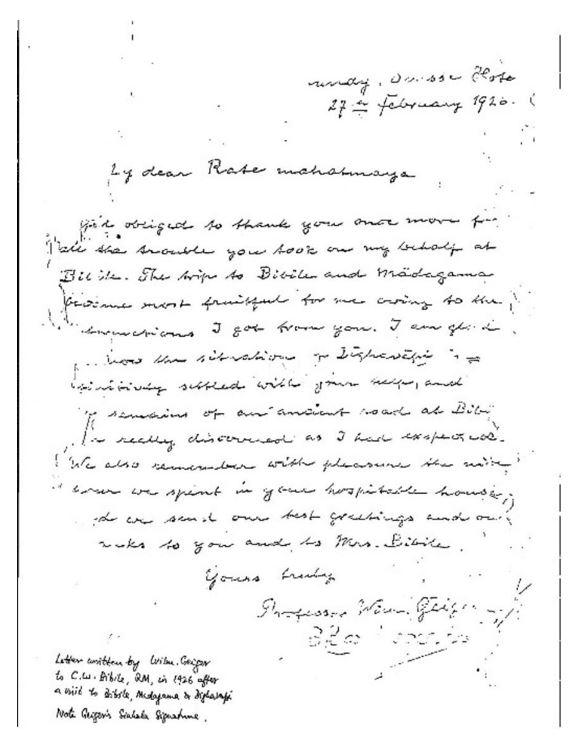

Above: Geiger’s letter of thanks to C.W.Bibile after CWB had arranged for Geiger to visit the Kalugalbemma in 1926.

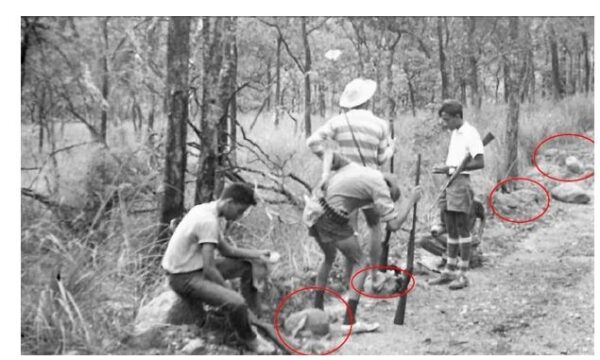

Above: The Author, grandson of C.W.Bibile, visiting the Kalugalbemma in 1966 with the same safety precautions as in 1926. Note the rounded stones which are the hallmark of the Kalugalbemma. Could these rounded stones have been the base stone- course of a road where the upper layers have disappeared over the centuries, or could this long north-west to south-east aligned stream of rounded boulders be a geological fault of some sort? No one seems to know. Of course, for the old Lankans to build their pyramid sized Dagobas and the great dams, reservoirs and long irrigation canals, they must have had an intricate system of sturdy roads to transport the heavy building materials.

Anthropologist Dr. Seligmann’s Map of the Henebedde Valley and the Veddah Caves from his 1908 Expedition when he was accompanied by Ratemahattaya W.R.Bibile, C.W.Bibile’s father. Note the spot from where the photograph below was taken of the full Samudra

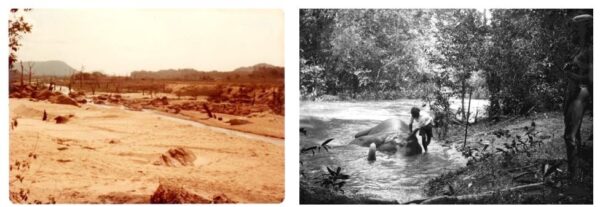

Above: “As the pent-up waters rose relentlessly over the monsoon seasons they submerged tens of thousands of acres of beautiful earth; and the historic lands around Nilgala, of Wellassa, and of the Maha Wedirata, drowned ”.

Above: The lakebed in the dry season seen from near the same spot as the full lake was photographed in the top picture.

Above left: The Gal Oya and the lakebed in the dry season, photographed at the location of the old Embilinna circuit bungalow. Above right: Embilinna in 1927 with its luscious riverine forest. The Bibile Walauwa elephant ‘Mudiyansé’, being used for the von Eickstedt expedition of 1927, gets a bath. The flooding of the terrain to create the lake killed off the trees.

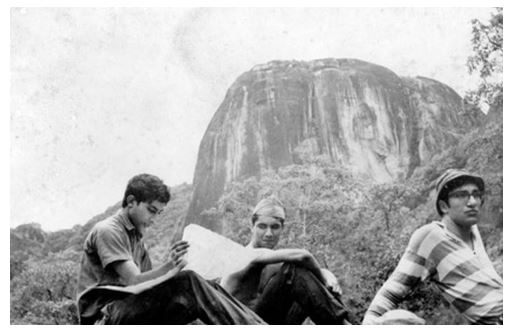

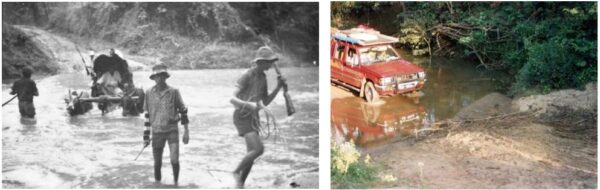

. Above: Camping in the Nilgala Frontier in the 1960s required walking the 15 miles (22km) from Bibile to Nilgala in a day, and total self-reliance in the jungle, including having a thorough knowledge of map readings and compass bearings for accurate navigation, as well as obtaining one’s own food from the jungle.

Above: Camping in the Nilgala Frontier in the 1960s required walking the 15 miles (22km) from Bibile to Nilgala in a day, and total self-reliance in the jungle, including having a thorough knowledge of map readings and compass bearings for accurate navigation, as well as obtaining one’s own food from the jungle.

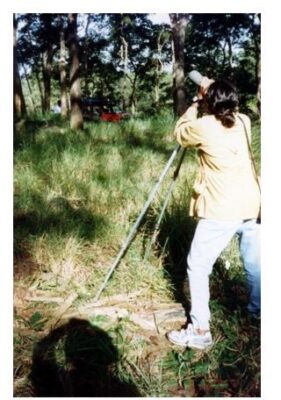

Above: Reading maps and navigating in an era before GPS was invented. Here, I am studying the 1”:1mile Nilgala Topo Sheet while seated below the brow of Bulupitiyahela (1770 ft) .

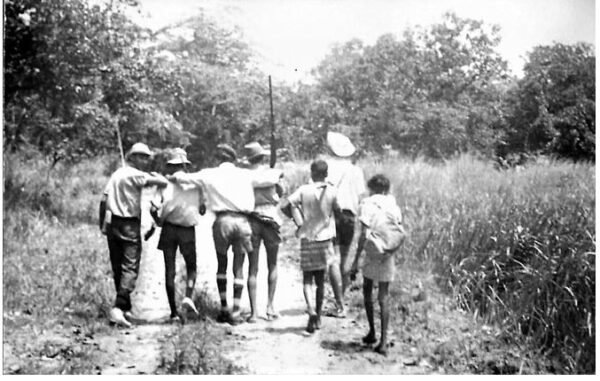

Map, compass, axe, gun, rod & reel: Our survival gear in the Maha Wedirata in the 1960s

Trekking into the wilds with a jaunty step

Above: Crossing the Pammedilla Oya, the halfway point on the 15-mile (22km) trek from Bibile to Nilgala: Here seen in the dry season with our tracker Podiappuhamy from Bulupitiya Village bringing up the rear, armed with his trusty 12 bore shotgun. He would not venture out of his home without the weapon. There were several streams like the Pammedilla to be forded in the journey across the well drained talawa to get to the Maha Wedirata

Below: Getting to the Maha Wedirata required the taking of many safety precautions against wild animals, and preferably, when we could afford it, transport of some sort for carrying luggage and provisions as it took the loads off our backs.

Bottom left, Crossing the Pammedilla in the rainy season circa 1966, with a bullock cart carrying the camping gear and provisions.

Bottom right, In 1994, in the comfort and safety of a 4WD with its roof-top sleeping quarters.

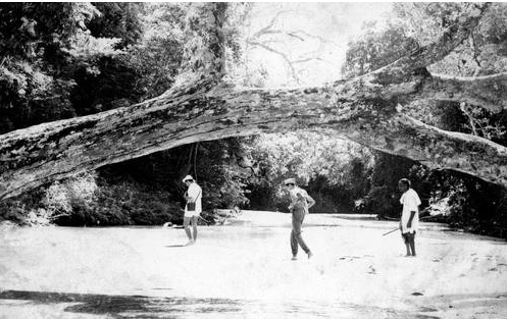

Above: Another stream on the way to Nilgala.

Above: The Nilgala Frontier is where the avifauna of the dry-zone, the wet zone and the mountain zone co-mingle.

It is a paradise for ornithologists.

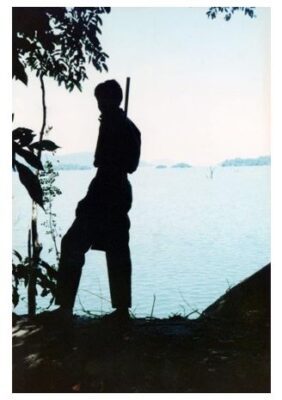

Above: In the 1990s, the Wild Life Department would provide an armed guard for protection during my foot-expedtions into the Nilgala Frontier and its Gal Oya National Park, whereas, in the 1960s, the Author and his fellow exploreres were free to carry their own licensed firearms into the territory.But after the JVP uprising of 1971, that was forbidden.

My faithful tracker Podiappuhamy (seen here in a turban) in the back of my 4WD in the Nilgala talawa. Podiappuhamy disliked vehicles and preferred to walk in the talawa with his loping-rolling gait and could cover about 5 km per hour on foot.

On one occasion I hired a tractor-trailer to go to Nilgala as the excursion group had weaker, less fit members. Those who know, know, that there is no bumpier ride than in the trailer of a tractor. After an hour, Podiappuhamy said he’d rather be thrashed by a wild elephant than go again in such a contraption !

This hardy soul, to whom I could entrust my life in the wilds, passed away before the end of the millennium, about the same time I was exiting Sri Lanka for good. With his passing, there died a body of knowledge that was irreplaceable. The younger generation, in my own experience, have no knowledge to navigate these still somewhat trackless forests, and have no jungle survival craft worth talking about.

Footnotes

Above is a general contour map of the Maha Wedirata showing points of interest and some of the dramatic peaks and valleys, and the overall terrain which made it inhospitable to both the Sinhalese and the foreign invaders. Even the British Colonial power left the Veddahs alone but gave them special privileges; one of which was the right to grow marijuana for their own consumption, an activity that could land any other Sri Lankan in jail.

The wild terrain depicted in the above map is seen in the following photographs. This territory is where the Veddahs gave refuge to the Kandyan Kings. None of the invading western armies dared to venture into this wild landscape guarded by the Veddahs.

The dramatic peak of Ulhela (1515 ft) dominates the scene as it soars above the surrounding jungle plains.

von Eickstedt on the Veddahs, quoting from the Parangi Hatane et al:

“And yet these ‘backward’ people … were among the most faithful servants of the King. To the Veddahs of Wellassa it is said were entrusted the King’s treasures, twelve of them being chosen to be the custodians and invested with silver girdles and canes embossed with silver, and a special dress to distinguish them from their fellows. They would stealthily enter the palace at night and interview the King when they desired orders on any matter affecting their charge.”… “When pressed hard by the invasions of the Portuguese which were soon to follow, it was to them that the King used to entrust the Queens, and they would shelter them in temporary huts, brightly adorned with greenery according to Sinhalese custom, constructed in the dense forest which stretched for fifty miles” ….“Later, under distress by the Portuguese the king would entrust them the queens who would be protected by them in an area of deep forest between Welasse and the first row of Batticaloa mountains. So the Wedda land was in a way the last refuge of the Singhalese kings.” – “And our King could no longer stay in the city, had no strength for the fight – but with his family, his precious gold and precious stones, with his slaves and his files and treasures – King Senerat then sought refuge in the districts of the Weddas, that was because his fame was darkened and his (religious) merit unsuccessful – and the courage of the men melted like wax in front of the flame of the imperious enemies of the Franks

“So the Wedda were powerless in the kings territory and the king was powerless in the wedda territory. Out of this specific and strong relations developed which could be described as a social symbiosis.”

– Baron Egon Freiherr von Eickstedt, 1927

The little patch of paddy at Nilgala, surrounded by the wilderness of the Maha Wedirata

Seen from Inginiyagala: Parts of the Maha Wedirata drowned under the Senanayake Samudra. The dramatic wild peaks are seen across the water in the hazy distance. Even today, it’s a mysterious land, probably visited only by a few people as it is still mostly inaccessible and remote and far from comfy hotels.

Above: The Author’s view of Ulhela on one of his expeditions to the Maha Wedirata. Fire destruction like this happens in the dry season.

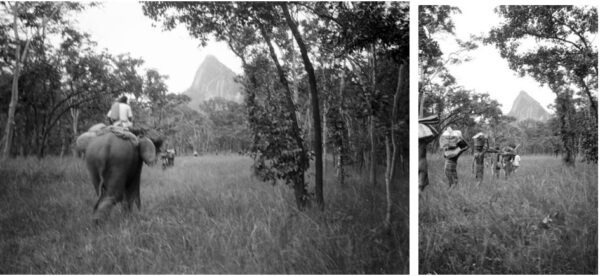

Above: Two photographs from von Eickstedt’s expedition of 1927 shows Ulhela dominating the route.

The left photo shows Ratemahattaya C.W.Bibile’s family elephant ‘Mudiyansé’.

CWB also lent the Walauwa horse to von Eickstedt. The elephant and horse (and even the Ratemahattaya’s palanquin or ‘Dolawa’) were more useful means of transport in the trackless terrain than any car of that era.

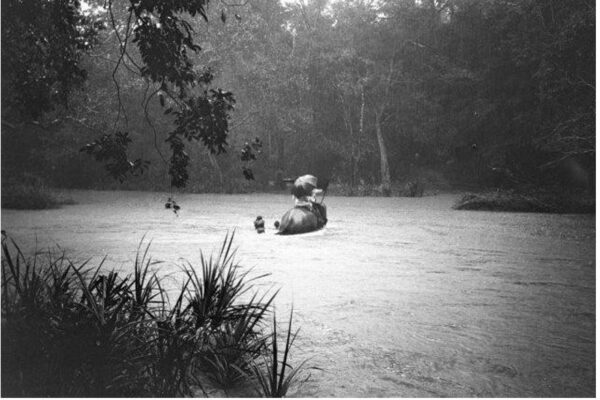

The Walauwa elephant crosses the swollen Gal Oya

von Eickstedt wrote in his field notes, inter alia: “ After a 3‐hour march through park jungle, the ford of the Gal Oya was reached. Underneath the deeply down‐hanging trees the murky gurgling waters flowed hurriedly and soaked the trunks, from the small islands, only bushes stuck out. Therefore, the horse had to be sent back to Nilgala, and the elephant under the Kovala was the first to steadily cross the stream. Then he had to cross the river six more times, under the heavy burden of our luggage – while the Haute Volée of the exped. (incl. servants) swang itself on his back and the porters, paddling at his side, clinched to the ropes as well as to his ears and tail. Three, among them the headman of Hamatulla with his picturesque cloth (he was Shikari and guide of the exped.), dared to cross the river swimming.: “